The Laurie Green, MD Innovator of the Year Award is given annually to a physician volunteer who exemplifies the transformation that MAVEN Project seeks in health care delivery. We are honored to present the 2024 Innovator of the Year Award to Claude Rogé, MD.

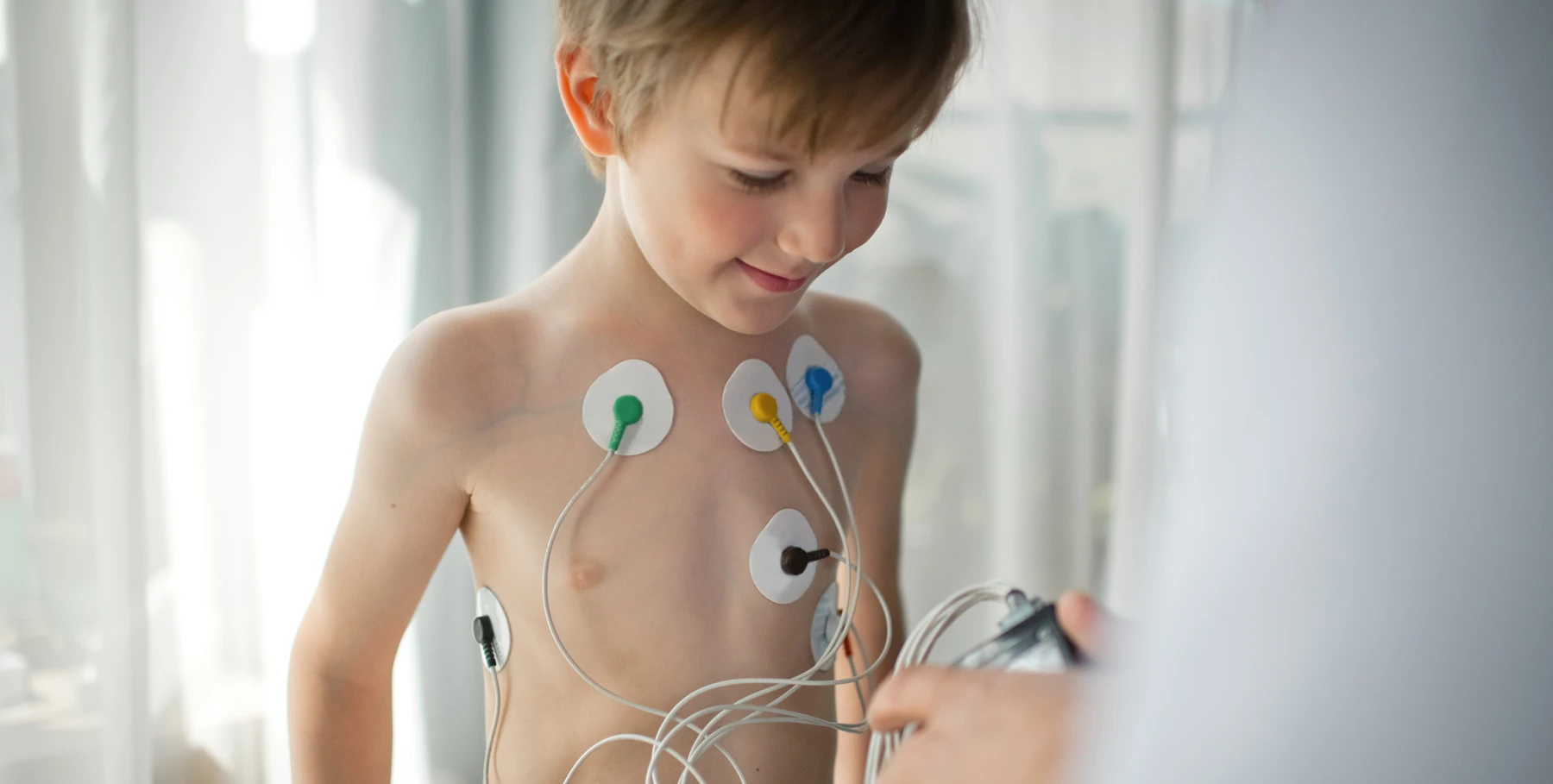

Can you talk about the need for expertise in pediatric cardiology in underserved communities?

Most community clinics only have general practitioners. They occasionally have pediatricians, but most of the time there are nurse practitioners or physician assistants doing family medicine. They are comfortable seeing children—as long as everything is going well. The good thing about pediatrics is usually, most things are going well. If something is wrong, it’s usually only one one organ that’s affected. It’s not like adults where everything is falling apart.

But it can still feel really difficult for the provider to decide, you know, am I dealing with a child who has a heart problem? Should I send them to a pediatric cardiologist for a consultation? If the answer is yes, it might take weeks or months to see one. It might mean traveling long distances and taking time off work—and all of that increases the family’s anxiety. Is my kid going to die of a heart attack? That’s the kind of thing that goes through their heads while waiting for a specialty consult.

In your own words, how does MAVEN Project bridge gaps in community health?

Community health providers deal with a ton of stress. They have to see patients, review and write up notes, deal with phone calls, and they don’t have a lot of time or resources. Even if they have access to platforms like UpToDate, they have to ask exactly the right questions, and it can still take a lot of time to find the right answers. So having immediate access to a specialist—I try to answer requests as soon as I get the notification—gives them and their patients exactly what they need.

This brings me to the advantage of MAVEN Project: we can tell primary care providers if there are red flags or not and help them decide if a referral is actually needed. Maybe the patient can be monitored at the clinic, or maybe they need outside testing to make sure it’s safe for them to keep playing sports. So we’re not only supporting providers but also patients and their families because now they don’t have to worry and wait for months to get answers.

What do you love about working in pediatrics?

I love working with kids rather than adults! Even when they don’t feel well, they like to play and have a good time. I can always try to be funny with them. They haven’t had enough bad experiences to be worried that they’re going to die from coughing, you know? As long as they can play and be with their friends, they’re good.

Can you share a particularly rewarding experience or success story from your work with MAVEN Project?

Most of the time, I reassure providers—don’t worry, you checked everything, I’m here if you have any other questions. But sometimes they need me to tell them that yes, a referral is appropriate.

I recently did a consult with a physician assistant who was treating someone with a relative who had died suddenly at 26. The patient seemed very healthy, but the EKG was borderline concerning with that family history. Community clinics have limited testing equipment, and you have to be extra careful with genetic conditions like this one. In that case, it made sense to send the patient to a specialist for further testing to make sure he was not at risk.

Are there any medical innovations you’ve observed over the course of your career that continue to influence how you practice and/or advise others?

After being at Yale, I went to UCSF for my pediatric cardiology training at the Cardiovascular Research Institute. They had one computer. It was in a small room, and you had to make an appointment to use it for 15 minutes or an hour. And of course all our notes were handwritten. Needless to say, things are very different now. Medicine has completely changed.

Another big change I’ve observed is the technical aspect of treatment. I used to work in the cath labs, and back in those days, it was strictly diagnostic. You would collect data, get blood samples, take pictures, and that was about it. Little by little, devices were introduced to actually treat conditions. These days, you can place a tube in someone’s vein, in the groin or the arm, and put in a device. The patient doesn’t have to go through general anesthesia or stay in the hospital for two weeks, which was the norm when I started out. Now, you stay overnight, or even go home the same day, and you might not even have a scar. The advancements in surgery have made a giant difference in my specialty.

A different kind of progress in general medicine has been the concept of questionnaires. When you see a patient now, you screen them for everything. You might ask about adverse childhood experiences, depression, anxiety, or history of abuse in the family. Using multiple, systematic questionnaires allows providers to detect issues that could have otherwise been missed. Before, this depended completely on the dialogue between the provider and the patient.

What accomplishments do you look back on with particular pride?

In October, School Health Clinics and MAVEN Project co-hosted an in-person CME conference. One of my colleagues, a pediatric nurse practitioner, originally had the idea, and I helped make it happen. We invited staff from other community clinics because we thought it would be good for local providers in our area a) to meet each other and b) get to know MAVEN Project. We had great speakers, physician volunteers with MAVEN, who led educational sessions, and we got really nice feedback afterward.

Another achievement that comes to mind is a grant that School Health Clinics received about six years ago to work with another organization to provide psychiatric care within our clinics. The organization provided their own staff, including licensed social workers, to work with both kids and adults on general psychiatry and more specific issues like addiction.

We had the grant for two or three years. When it expired, we decided that it was so helpful to our patients that we really wanted to keep the program. But it’s impossible for us to hire psychiatrists. So two MAVEN Project volunteers, Dr. Musacchio and Dr. Smith—for pediatrics and adults, respectively—are helping us continue to offer those services. So that’s wonderful.

Why is MAVEN Project’s model, which focuses on peer-to-peer connections between practitioners, the most effective way to improve patient outcomes?

If you’re a provider in a small clinic in a remote area, you don’t have a lot of options for help. You can try calling the specialist in your area for advice, but you might not reach them. You can go to the web for medical research, but you have to know how to decipher what you find. You can’t present that system with a patient; you’re just collecting data and seeing if it can apply to your patient. There’s a huge difference in being able to talk to someone, especially someone like me, who has been practicing for a long time. We have the practical clinical experience to help newer providers manage their patients. This is so much more valuable—and efficient!—than trying to figure it out yourself by searching through all the data you can find. Your patient gets the advice or the treatment they need, and now you know what to do when those issues come up again—and they very likely will!